This blog post can be read in French here.

Digital decolonisation is generally thought of as breaking the monopoly held by a select few nations on digital technologies and platforms, to afford countries more control and autonomy. To achieve digital sovereignty, Digital Public Goods and Digital Public Infrastructure are becoming increasingly popular approaches.

However, in a recent interview with the University of Oxford for the Global Economic Governance Programme, I argued that digital decolonisation is a two-way street.

Beyond technology choices,the path to autonomy demands a change in mental models: dispelling the myth that what works in higher income countries is necessarily what all countries should aspire to replicate. To me, digital decolonisation is also about countries feeling empowered and having the capacity to design digital services that work for them, within their context and culture.

Public Digital’s ongoing work with the Digital Governance Unit (DGU) of Madagascar, as part of the World Bank supported programme PRODIGY, on their government portal, is a good reflection of that.

Torolalana: Madagascar’s government portal

Government websites are usually the single site for users to access trusted and up-to-date government information as well as public services, like applying for a passport, or filing a tax return. They have the potential to significantly shape and improve the interactions of citizens with their government.

The UK’s website, GOV.UK, has without a doubt been a major inspiration for governments around the world. It has demonstrated the benefits of providing information and services on a single website, designed around the needs of users rather than government organograms.

But as one of PD’s founders, Tom, has written about, a focus on online channels carries risks.

When we started our engagement with the DGU in September 2022, the Malagasy government portal, Torolalana, was a working version of one of the many GOV.UK-inspired websites around the world. However, focusing only on the website at the expense of other non-digital platforms which connect citizens and government risked excluding the 80% of Malagasy citizens who do not have internet access.

In our work with the DGU, we turned to other models for inspiration beyond GOV.UK, looking at the governmental websites in a variety of economic contexts, including Rwanda’s portal, Irembo. We pivoted towards a vision for Torolalana that would make public services more accessible to all citizens, rather than only those with access to websites.

We quickly realised that for this to happen, Torolalana had to leverage multiple channels, including an in-person channel such as help desks, mobile agents, or call centres.

The Mahatoky service: In-person citizen helpdesks

This new vision was translated into a roadmap for Torolalana that was iterated and refined as the team learned more about the users’ needs: what Malagasy citizens really needed from their governmental portal.

Developing the roadmap for Torolalana

To discover the needs of citizens in relation to accessing public services, we began by conducting user research.

Among other findings, the research revealed that post offices were a potential partner for the DGU in providing assistance on public services. They are widely trusted by Malagasy citizens and have already begun to diversify the services they offer.

Informed by this discovery, the DGU chose to partner with Paositra Malagassy (Madagascar’s postal services), with the support of the Ministry of Digital Development, Digital Transformation, Posts and Telecommunications (MNDPT). Together, they were able to design a new in-person channel for public services: the Mahatoky service.

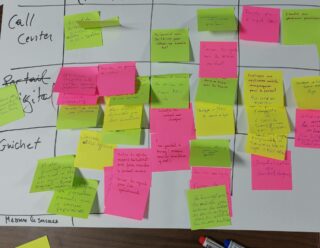

Developed as an initial prototype after a design sprint with Public Digital and the DGU, the Mahatoky service (‘Mahatoky’ meaning ‘trust’ in Malagasy) takes the form of an in-person help desk located within post offices.

Here, citizens will be able to access information about public services, such as guidance on requesting a building permit, information about government benefits, or financial assistance for students. Postal agents operating the help desks will be trained and provided with the tools to help citizens better understand and access public services.

As the in-person channel of Torolalana, the Mahatoky service will build on the trusted relationship that already exists between citizens and postal agents.

The future of Torolalana

In its current form, Torolalana is a web portal that serves as a guide for citizens to access public services. Likewise, the early roadmaps for the Mahatoky service focus solely on providing information and guidance. However, as Torolalana evolves to incorporate single sign-on to enable access to online public services such as creating a company or obtaining a vaccination certificate, so will the rollout of the Mahatoky service.

The DGU aims to develop a dedicated Torolalana platform for Mahatoky agents working at help desks to allow them to perform transactions or submit requests, such as registering cattle, on behalf of citizens. This will give all citizens, regardless of their internet access or digital resources, equal access to Madagascar’s public services.

Employees of the Paositra Malagassy in Madagascar

The path to digital sovereignty is a challenging one. It requires considerable investment and capacity, and it does not happen overnight. But small steps in the right direction, like the work of the DGU on the Mahatoky service, deserve to be celebrated. After all, every journey begins with a single step.

We are proud to have the opportunity to help the DGU build capacity to design public services with the needs of the Malagasy population at heart.

To hear more from us on internet-era ways of working in public and private organisations, subscribe to Public Digital's fortnightly newsletter.

No comments yet